How can we ensure that we function optimally and feel great as we age? What makes a durable human? How do we combat the effects of our modern, more sedentary ways of being on our body’s need for activity? These are a few of the questions that this week’s guest, Dr. Kelly Starrett, can help us answer.

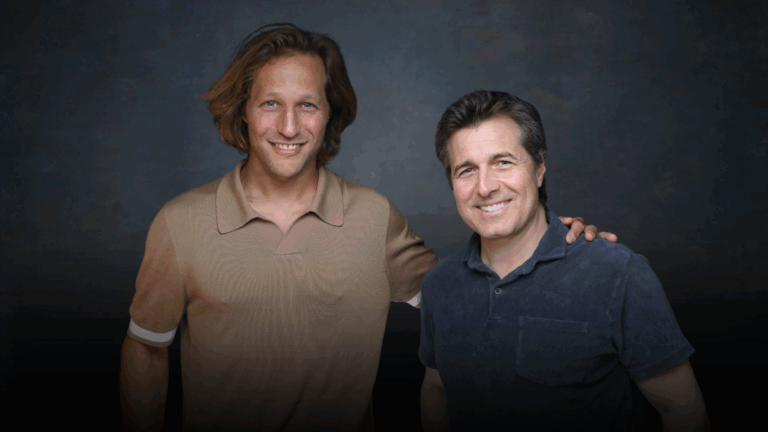

Known as a “mobility pioneer,” Kelly’s career as a doctor of physical therapy has led him to some extraordinary places. He consults athletes and coaches from the NFL, NBA, NHL, MLB, U.S. Olympic Team and CrossFit; he works with elite military personnel; and he consults with world-leading corporations on employee health and well-being. Kelly’s work, however, is not limited to coaches and athletes – he believes that every human being should know how to move and be able to perform basic maintenance on themselves.

The author of two best-selling books, Becoming a Supple Leopard and Ready to Run, and co-founder of the mobility training platform, The Ready State, Kelly’s work offers comprehensive tools and foundational wisdom to optimize movement and unlock pain-free performance. His newly released book Built to Move, which he co-wrote with his wife Juliet, guides readers through the ten essential habits to help you move freely and live fully.

In this thought-provoking conversation, we explore why intentional movement is so vital to our well-being over time, best practices for managing stress and pain, and how to formulate a plan for the long game.

“If we can start to empower people on small behaviors that they can integrate into their life, they will feel better and have better access to their range of motion so they can do the things they want to do.”

In This Episode:

Built to Move

I thought stretching could really use a face lift. I think with all of the changes in our lifestyles, being impacted by sleep, inactivity, the food choices, the stress, the work, we’re starting to see that for us it’s starting to impact our ability to move freely and in a pain-free way. So what we’re trying to do with Built to Move is establish some benchmarks and some vital signs that anyone can use to say, “Hey, how is my lifestyle impacting my way to move through the environment?”

A reframe on movement

One common misconception of movement is that one-hour exercise three times a week solves all our problems. We want to expand what people think about in terms of how their bodies move in their environments to 24 hours. So a physical practice means what happens when I wake up to when I go to bed. We want to start to view exercise as an extracurricular. So if we can start to empower people on small behaviors that they can integrate into their life, they will feel better and have better access to their range of motion so they can do the things they want to do.

How professional kayaking shaped his view

Understanding a little bit of my framework was through the lens of being a guide, this chaotic environment where we can’t control everything, having to rely on each other. And then coming into this professional sports world where my experience there was all reactive, that I did all the things you told me to do and I got injured and I got burned out. And I saw that happen over and over again and I started asking a lot of questions. So how could we have prevented these things? How many eggs have to be broken? We’re just like, “I don’t know. The egg wasn’t very strong. We threw it against the wall a bunch and it broke.” And I think that really was the genesis. I don’t know if I’ve even said this before. I think that was the first time I realized, “Hey, I wonder if there’s something we could do to have these inputs on the front hand to build better resilience, better performance guarantees instead of just waiting for something to go wrong.”

How does your body operate under pressure?

What I had come to understand was something that recently was said by a coach named Frans Bosch who says, “There’s more variation in waltzing than there is in sprinting.” And by that, what he’s saying is at high speed, we see a lot of practice look the same and that low speed doesn’t really matter. You can get away with a lot. And I think the allegory for people here maybe is that the things that work for you suddenly stop working for you in really stressful situations or injury or trauma or death or loss or you’re losing or your business isn’t doing well and you don’t have a plan…there’s a lot of tolerance in the system when the stakes are low. You don’t have to manage your sleep. You don’t have to manage your range of motion. You don’t have to manage your nutrition or hydration or mindset or downregulation. You don’t have to do those things. You can go drinking and get up and do your job and not have slept and eat like a spoiled teenager and still be pretty rad. But all of a sudden, when the stakes get higher, we find that the best practices really all start to approximate each other because there’s less tolerance for all of that undisciplined behavior.

Translation from sport to household

My wife and I have come to believe that if we don’t take those lessons in sport, especially around my area of expertise, the body and transmute them to our households, our families, then this is just circus…We said, “Wow, we’re putting all these men and women and people through these experiences. Maybe we can learn something and actually transform our families and our communities.” And that’s where I am today. It’s still fun to work here, but boy, wouldn’t it be great if we could take those lessons and transmute them into having kids who feel better, who sleep better, we see more durable tissues, et cetera.

His guiding philosophy

I think that every human being should know how to take care of themselves. So a long time ago, I said, basic maintenance. You should be able to perform basic maintenance the same way that I think we ask, “Can you self soothe?” I mean, if I just leave you out in the world, what are you going to reach for bourbon, Ibuprofen? Are those your strategies?” Those strategies work for a while till they don’t work.

Become a supple leopard

Our first book, we called it “Supple Leopard.” One of our friends with was a Seal who got injured, shot. And one day he pulled me aside and he’s like, “Kelly, the leopard doesn’t stretch.” And I was like, “Well, Andy, A type one error in you’re thinking, you’re not a leopard. I don’t know if you know this. And B, that leopard can attack and defend at full physical capacity. It doesn’t have to activate its glutes or warm up or go through a pre-cog energy thing. It doesn’t have to snack or preload carbs. It just is a leopard.” So what happens if we just gave people access to their range of motion again? Then suddenly we can give them more movement choice, we increase movement solutions and we start to untangle a whole lot of things. You know, you can start from the top down, the brain and the mind or you can start from the bottom up but we’re going to get to the same place eventually, we have to.

What are you practicing?

Practice doesn’t make perfect, practice makes permanent. And I’m like, “Well, what are you practicing for hours and hours and hours? Are you mouth breathing? Are you slunched over? Are you taking shallow non diaphragmatic breaths? What are you practicing?” We know that you’re going to default to your most practiced patterns. This is in training, why I’m trying to induce load and stress to uncover patterns and practices and behaviors that don’t serve you as well as a different set.

Create support systems

One of the things that I realized 10 years ago was that I needed to create better support systems for me. In that recovery strategy, I had to make sure I had other men, particularly non wife, other friends, of which I could be vulnerable and ask for help. I needed coaches. I mean, in the meantime, we were so burned. We were starting this business and we had two kids and two corporations and, man, I was spread so thin and burned out. And no wonder, which that’s like you’re going to crash this family into the ground, you maniac. But one of the things that has happened is creating this relationship with my friends. We have been talking about George Mumford a lot. This interaction, the space between stimulus and response, has been a really important concept for a lot of my friends.

Your best is already within you

Carl Rogers is in my blood, which is, boy, the better version of me is here. All I have to do is work towards it and why can’t I be capable of infinite growth, infinite, all of the things. I have to be mindful of the whole system. And not so much that I’d get away from actual deep practice. You just got to go do the thing but you have to be aware of the thing.

Objective measures

When we’re working with performance, my objective measures are, can you do what your body is supposed to be able to do? Does your shoulder have as much range as it should? Can you control that range? And that’s the second piece. And we do that in the language of strength and conditioning, this formal movement training. It’s like, here’s what your body’s capable of, let’s challenge it. But ultimately the expression is, what do you want to do with that thing? Wattage, poundage, output, all of those things. The test is, oh, you’re a master? Go ahead and spend a weekend with your family. Let’s see how zen you really are. You can practice it. You can do drills to get better at it. It’s the application of the thing. My two objective measures really are, can you do what your body’s supposed to do? The wattage and improvement in power and output is how I test this process.

Be proactive, not reactive

The problem is, unless someone says to you, you should keep an eye on this, how are we going to do that? How are you going to fit this into your busy life working, single mother? How are we going to fit this into children? What we find is we’ll wait around until you fall. We’ll wait around until we have a whole bunch of lagging behavior, lagging indicators. We can wait until you have a hip replacement or wait until you have hip pain or your back hurts. And then we can be like, oh, your hips are stiff. And you can be like, why didn’t anyone tell me? I had all this time and I was interested in this, and I’ve been exercising and going to Peloton, what’s the problem? The problem is we didn’t tell everyone, here’s what we should keep an eye on. Here’s a simple benchmark. Imagine if your physician asked you to do this during your annual physical. A physical should actually be not just what’s going with your blood panel and your blood pressure, but how you actually move too.

Barriers to adherence

Just the number of steps between you and doing something. And we’ve seen that from the research around garbage and Disneyland. If I have to walk somewhere to put something in a garbage can, I’m not going to do it. If I can see a garbage can, I’m going to walk over and deposit my trash in the garbage can. If we’re asking people, and you know this because you have teenagers. But if I ask someone to engage in a healthy behavior, for example, that they have to call someone, set up a time. The more barriers or the more steps, the chances of me actually doing the thing just starts to diminish, becomes approximate to zero. And eventually you’re like, I don’t even know where to get started.

Movement extends beyond just your body

Your hip range of motion is important to me because you can’t do the thing you want to do suddenly. You can’t play basketball the way you want. That impacts your relationship with your friends, how you express yourself. There’s a whole lot of psyche attached to this body in terms of the way that you interact with your community, in a way you define play. Just that alone, if I can’t play. One of the most important pieces of advice we give when people are injured, I’m like, do not separate yourself from your team. Go bring the bike and do your rehab with the team. Go be around the team. Why would I pull you away? There’s a reason why athletes fear injury and the training room is death, because we’ve culled you out of the herd.

Finding the pain

What I want you to do is I want you to look for the spots that feel awful, and then I want you to work on them until they feel like Switzerland. And if I push it, wait for it, if I push on something that feels great, keep doing that…So we can either use that pain or we can use that pleasure response, but really what I want people to understand is when you experience pain with pressure, that’s a spot that could be changed. That’s a spot that your brain may pay attention to and that can be a breadcrumb around restoring function or restoring sort of positions or tissue slidability.

Stack your soft-tissue work with breathwork

Soft tissue work is a wonderful way to down-regulate. And that when I’m feeling out of control or I’m feeling stressed, if I engage in self-massage and I’m watching my breath, after 10 minutes, man, I feel like a different person.

Breath is the foundation

We start to see this trinity of neck, shoulder, upper back. What’s the easiest and fastest way in? What’s the first movement of the spine? It’s the breath. It’s not walking, it’s not crawling, it’s breathing. If you come to me with a little back pain, guess where I’m going to start, breathing. We’re going to start by showing you how to get more movement into the trunk, into the spine, so that the brain says, this is not a problem. We can start to restore and re-normalize your trunk function. So suddenly that breath became the through narrative for everything that I do. In fact, when we start with people, and I’m talking about either Tour de France or Olympic weightlifters in the Olympics, we talk about breath.

Be durable

My wife is a two-time cancer survivor, I’ve had my knee replaced, had a bunch of friends die kayaking. We want to be as functional and rad as we can until we can’t… That’s really how we feel. The hits are going to come. So it’s not about living to be 150 years old, it’s about being durable enough to take the hits that are coming.