20-time Grand Slam winner, Roger Federer and 14-time Grand Slam winner, Pete Sampras, have at least one common thread in their tennis careers and he happens to be our guest for this episode.

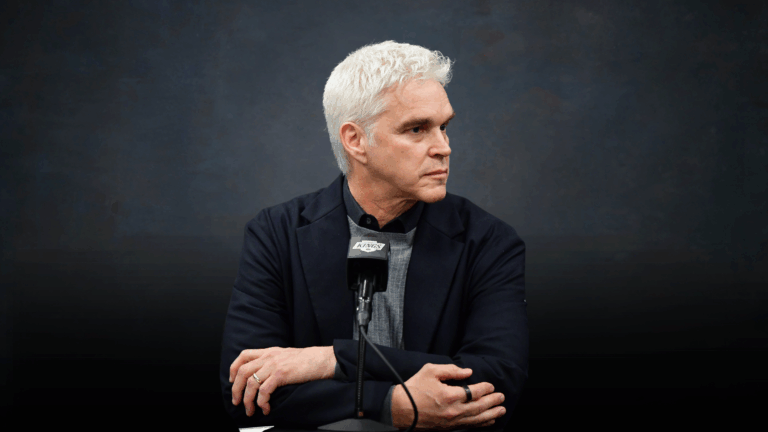

Paul Annacone is a former touring professional tennis player who began his coaching career in 1995 working with the legendary Pete Sampras. Since then, he’s become one of the most respected mentors in the game, coaching Federer, Tim Henman, Sloane Stephens and, currently, one of USA’s top-ranked players, Taylor Fritz.

Paul’s book Coaching For Life: A Guide to Playing, Thinking, and Being the Best You Can Be, is an autobiographical exploration of his experience inside the sport of tennis; more importantly, it’s a compilation of the lessons he learned along the way that are applicable to our own day-to-day life. His front row seat to arguably the best in his game has given Paul a true understanding of some of the guiding principles that live in the heart, and the head, of a true champion.

This is an incredible conversation. Paul and I dive into the interesting transition from player to coach, the importance of knowing who you are, what he thinks about failure, and what he believes separates the greats from everyone else.

“How good are you on your average days? My mantra is: Every player has a handful of great matches during their career, and a handful of garbage. The rest is who you are. Show me who you are in the middle.”

In This Episode:

Going from player to coach

One of the hardest things for me, Michael, was actually the initiation to go from a player to a coach. Because as a player, you feel like the perception is you have so much control over so many things when in actuality, you and I both know that’s not the case. You have control over many things, but when you become a coach, you have control over even less things. And so to be able to transition into a stand and try to get your point across and in an individual sport, I think it’s most challenging because I think if you want to be good at it, you have to figure out, number one, how to get buy-in from the player, which means, how do I say what I need to say, but the way they’ll receive it. And I think that’s a little different than team sports. I think a lot of teams kind of go into the coach’s philosophy. You go into the philosophy of the New York Knicks coach or coach Carol or somebody else in the NBA or NHL. That’s the philosophy you mold to as a tennis coach. It’s one on one. So you tend to have to figure out the person and then get the message across that way.

Knowing who you are

I don’t think you have to be totally tunnel vision and all about you, but you have to know yourself. And my biggest philosophy about maximizing your potential for anything that you do in life, and you would know this better than I, is you have to know your identity. You have to know who you are, what makes you work, why it makes you work, and how to stay within those parameters so that you can set up a structure that gives you the best chance to maximize whatever your goals are, both quantitative and qualitative. So I’ve been really fortunate that I’ve had a lot of people teach me along the way, and one of the reasons I still do it is I love to learn and love to hear and still love to think and teach.

Honesty and feedback

Look, the old funny cliche is denial isn’t a river in Egypt, is it? Denial’s definitely not a river in Egypt. And unless you can fully understand your strengths and your weaknesses, I think you’re limited. And I think sometimes great athletes, most of them I’ve been around, are pretty stubborn. So sometimes you have to be able to show them in a constructively critical way. Some of the foibles and everyone I’ve been around, I’ve been fortunate enough that they absorb it. You don’t slap them in the face with it, but you get them to understand.

Coaching identity

As a coach, I think you either have to help define the identity for the player as they’re younger and evolving or accept it and then manage that identity to figure out what components of that you need to work on to help them maximize their skillset.

Fulfillment outside of winning

Luckily, I’m fortunate enough to do some work with Southern Cal Tennis Association. I get to talk to some of the parents and I said, “If your child is merely focused on winning the tournament every week, that is a recipe for disaster.” I said, “I’ve been around for a long time. Every tournament I’ve been to, every person leaves pissed off except one every week. That’s not great odds. So you better find other ways to get fulfillment.” Of course, you want to win every tournament. If you don’t, then what are you doing there?

Head, heart and talent

I have a little unscientific model that I have in my heart that I make up an athlete and a human being by, the head, heart, and talent. Head is your ability to think through adversity, think through strategy, all the what ifs, all the things that are going on in the heat of the moment. That’s the head, your head. How good is your head on the scale of one to 10, then heart is a very simple one. It’s how well can you unconditionally compete no matter what. It’s broken foot, your dad just died, dog ate your … It doesn’t matter. That’s your heart, one to 10. And the last part is just the physical attributes that come into play, racket skills, athleticism. So those three components in me make up the player and the human being.

Practice

You don’t practice hard to play perfectly. You practice hard and more importantly, smart so no matter how you play, you react unbelievably well in that moment. So when you win two and two and you play great, I’m happy for you, but that’s easy. I don’t care. Show me what you do when your ankle’s sprained. Show me what you do when you broke up with your girlfriend. Show me what you do when they lost your … And that to me is what I have found personally and experientially What’s so amazing about great players. I mean, I cannot believe some of the stuff that I’ve seen Sampras accomplish and Federer accomplish when unbelievable adversity.

Fear of losing (and winning)

Sampras might be the best athlete I’ve ever been around that is able to put the result first. This is, “I want to win,” like I told you about at the beginning, “I want to win as many majors as I can,” and be able to handle victory and defeat without fear. Sounds easy. I talked to a college basketball coach about this once and they said, “What have you found about the …” I said, “They aren’t afraid to win. And they’re not afraid to lose.” If you just thinking, “I’m like that.” Yeah. You walk onto Wimbledon Center court under the archway with 14,000 people there by yourself playing a final and eight million people watching and hear the umpire say, “Players ready, play,” and hear dead silence. That’s my first reality of what deafening silence is. Now you do that and tell me you’re not afraid. And then do it in the semi-finals or the finals. There are not many human beings that can do that and still succeed and still excel with what their skillsets are.

Boiling it down

For me, so much of it is back to the core stuff: Knowing your identity, what can you do under pressure, understanding that those moments are everyone’s, you’re not in isolation, and how do you do what you do best in that moment without taking high risk?

Roger Federer’s perspective

Two years in a row at the US Open, [Roger] lost in the semi-finals to Novak Djokovic after holding match points. Two years in a row. And I was with him both years. And literally, when I walked out of the stadium after the second year, I was like, “Did that really just happen again?” And then after that match, he was back at his hotel room four hours later on the floor playing and laughing with his daughters, with his twins. And I said to him, “Can I talk to you a little bit later tonight just about them?” And he said, “Sure.” So we went in another room and we were just sitting there for a few minutes and I asked him about what happened and whatever. And his response was, “Yeah, I know. Such a bummer.” He goes, “But I’ve won a bunch of matches where I never should have won. So that stuff happens sometimes. So when’s the next tournament?” It was literally like this ability to go, “Yeah, God, that was such a bummer. But man, there was so many matches where I had no right winning and I found a way to win. And man, it ends up …” I’m paraphrasing, but that was the theme of it. And I was like, “Dude, I could barely walk and I wasn’t even playing.”

Making a plan (and adjustments)

I’m a big planner. I believe in making a plan, but I’m also not naive and I know that plans need to change oftentimes because of some things that are in control and some things you’re not in control of. And so you have to commit to your plan. And then you have to be smart enough to know when there needs to be tweaks to it. You would probably know this better than I do, but good team around you, right? Good coaches, assistant coaches, good CFO, good COO. You have to have the right people around you to know when you make the little adjustments. And none of those adjustments can come from panic or insecurity. That’s why it’s also good to have the good team around you because you reassure, you stabilize who you are and what you’re doing, but you make subtle adjustments.

Overcoming adversity

My first two questions to address this are, what are your goals? What do you want to achieve? Tangible, intangible, quantitative, qualitative. And then, if it was off tennis, it was something else, it would be, okay, what are the operational needs to meet those goals? Okay, so then I would talk about that. And then I would find out historically and currently, what is the adversity that you’re facing that’s a deterrent to all that stuff. And then when you get into those, I would then talk about skills to overcome that adversity, the skills to overcome it, and the tools that are attached to overcome it.