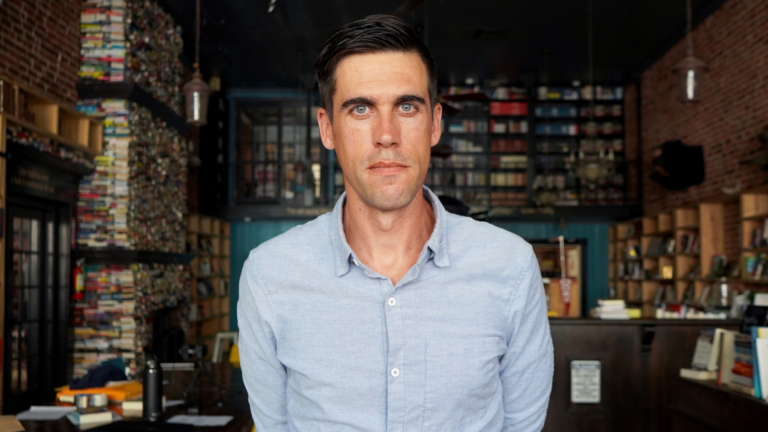

This week’s conversation is with Steven Kotler, a best-selling author, journalist, and one of the world’s leading experts on flow and human performance.

Steven has spent three decades teaching people how to achieve peak performance, and of late, putting his own advice into practice as documented in his newest book, Gnar Country: Growing Old, Staying Rad. In it, Steven challenges us to test our own limits as he himself sets out to become an expert skier at age 53.

Using his understanding of embodied cognition and flow science, he puts theories and his own body to the test in order to challenge the perceived limitations of peak performance as we get older.

He’s authored fourteen books, eleven of which are New York Times bestsellers. He’s been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize twice, appeared in over 100 publications, and his work is translated into over 50 languages; and yet, Steven’s appeal comes from far more than a list of very impressive accolades. While endeavoring to help others be at their best, he puts his own teaching into practice so his perspective isn’t simply scientific, it’s personal.

As you’ll find out in this conversation, Steven embodies true grit and refuses to allow getting older to hold him back from achieving his highest potential. I think we can all find inspiration in these insights from a real badass who’s living life to the fullest and inviting you to do the same.

“Mental high performance is the ball game, and if you’re not training it, you’re going to get your ass kicked.”

In This Episode:

Shattering the traditional theories of aging

Most of us grew up with the traditional theories of aging, which is what I like to call the long slow rot theory. It’s the idea that our mental skills, our physical skills, they decline over time. There’s nothing we can do to stop the slide. And yet there was stuff I was following in flow science and in related fields like network neuroscience, neurodynamics, and embodied cognition and some whiz-bang stuff. All of it basically said, hey, wait a minute, everything we’ve heard about performance in the second half of our lives is wrong, is wrong. For example, the long slow rot theory, all our skills decline there’s nothing we can do to stop the slide. Partially true. Our skills do decline over time, but it turns out they’re all “use it or lose it” skills. So if you never stop training these skills, you can hold on to them, even advance them far later in life than any even thought possible. And that also includes flow, right? Flow is really important to successful aging, performance aging, all those terms, but our access to flow declines over time. But it’s, again, trainable.

Teaching old dogs new tricks

The classic phrase is you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. Well, I was reading all this stuff, and I was like, wait a minute, if this stuff is right, at least in the lab, old dogs should be able to learn new tricks – including really, really hard tricks.

The impetus for his new project, Gnar Country

All I knew is that what the research is starting to show is that people over 40, over 50, there are cognitive superpowers that start coming online in those decades. And everything I’m reading says, oh my God, you should be able to really learn difficult skills laid into life. The big saw was the motor learning window, which supposedly slams closed, and that’s also not true. It’s that when we’re kids, we predominantly learn through playing. And what changes so much in adulthood is we start learning in a radically different way. Yes, the motor learning window does thin and there are shifts, but it’s actually the way we approach learning that changes the most. And so all this stuff was saying, “Hey, wait a minute, we should be able to do this.” I wanted a way to test it, is part A, right? And I decided to test it by teaching myself how to park ski.

The hardest parts of this project

One, it was once I started having success, the addictiveness of success was crazy. Progression is so delicious. And the other thing was when… And I didn’t know this. I could have probably talked to anybody I knew who would’ve told me this, and I just didn’t know. I didn’t realize that when you… Even if you do go up against really hardcore, scary things over and over and over and over again, and you win at them, you’re successful, which I was most of the time, you’re still going to get PTSD. It’s still going to affect your nervous system in that way.

His goal wasn’t just to learn how to park ski…

There are genetic changes that happen as you age, of course. Certain genes are activated only by experience, so it’s actually epigenetics. And there are changes on how the brain processes information in our late forties and fifties. And it’s really the two sides of the brain that start to work together really well, like never before. And the brain starts to recruit underutilized areas and regions and build backups and redundancies and things like that. And as a result, we gain access to whole new levels of intelligence, creativity, empathy and wisdom. Hugely important trait. So one of the reasons I knew that, especially that I could learn to park ski later in life was the heightened creativity that you actually get. And the heightened wisdom. The heightened wisdom means more emotional control, ways to keep myself safe that maybe I didn’t have access to when I was younger. So I thought there were certain things from this pool working at my advantage. And I’m a writer. I want access to new levels of intelligence and creativity and empathy and wisdom.

Key ingredients in a high performance life

Without regular access to flow, you’re not doing it. But almost every one of them, they’ve either got a best friend or a girlfriend or a spouse or a boyfriend. There’s somebody who is solving the cognitive load problem. There’s no way that… That’s part of the hard… Like when you’re trying to do that at that level, you can’t hold all the rest of your life in your head. Literally, you’re up against a cognitive load wall. So there’s got to be somebody who’s filling that gap. And there’s got to be a lot of flow in a tight loop, because otherwise you can’t keep going. The other thing is I always think there’s a little. There’s always a little extra. It’s a mission.

Expertise in wisdom

The greatest defense against Alzheimer’s and dementia and cognitive decline is literally expertise in wisdom. In fact, Yaakov Stern, out of Columbia who did some of the early work on this, he did a really famous study when he was looking at leisure activities that increase expertise and wisdom. So things like doing puzzles or having rich intellectual discussions with your friends or reading or those sorts of things. You get an additional 8% protection against Alzheimer’s, cognitive decline, and dementia for every additional sort of expertise skillset… Really, really neat finding there. So expertise in wisdom, lifelong learning, progression is literally how you have to preserve brain function.

Motivation by progression

Nothing is more demotivating than saying, “I’m going to go here and and learn this,” and you don’t. In fact, I found oddly, one of the easiest ways to not learn how to do something while skiing is to turn to my ski partner before the day begins and say, “You know what I’m going to definitely do today? I’m going to get my switch 180s down, and I can do 10 of them, at least, 20 of them today.” And at the end of the day I’ll come and I’ll realize I hadn’t even done one. It’s almost a guarantee if I say it out loud, it’s almost a guarantee that it can’t happen.

The infinite games

My buddy, Michael Ward, one of my closest friends has been teaching himself how to play the guitar for four or five years now. And he says, “The best thing about teaching myself how to play the guitar is I’m never going to run out of guitar. I’ll never run out of guitar. There’s an endless amount of that shit I can keep. I don’t run out of anything. I’m going to keep learning, keep learning, keep learning.” I think of skiing that way, writing that way. I actually think of marriage that way. These are the infinite games, but their progression is built in and you don’t win. There’s just the progression. And the other thing that is weird also is, to me, there’s a relationship between progression and expectation that kind of destroys more good days than anything I know. Which is going into, it could be a writing activity, going into a mountain and expecting a certain level of, “You’re going to make this much progress today.”

Progression is empowering

On the other side of a flow state, complexity goes up, adaptability goes up, mastery increases, wisdom goes up. And so Csikszentmihalyi is considered the major driver of adult development. Other people have talked about it as always as an evolutionary side of mastery. When you get into a flow state, it’s a sign that you’ve actually mastered skills. I think it’s definitely a sign of progression. That’s for sure. But the thing that I think is so neat about progression is it’s so empowering.

Translation of new skills into other areas

We process financial fears and money, you know this, in the same structures that we process physical fears. So there’s no difference in the brain between physical pain and financial pain. And it doesn’t appear there’s much of a difference between physical pain and financial pain and social embarrassment, shame, all that stuff. Which certainly all creatives are going to face when they bring their stuff into the public eyes. So no. And that’s what I like about it. And you know as well as I do, this doesn’t always translate. You and I both know members of the special forces or professional athletes who try to transition to the real world and they go into a boardroom and fall apart or they can’t do it. But those that stick with it end up really kicking ass. And the reason is the skills are transferable. It takes a while to figure out how to transfer. Not everyone sticks around long enough to really be able to figure it out. But, the skills are transferrable and the patterns are the same and the learning patterns are the same. And the order is always crawl, walk, run. It’s always going to suck to be a beginner. It doesn’t matter whether you’re learning a hard physical challenge.

A formula for peak performance aging

If you want our rock till you drop, you have to regularly engage in challenging social and creative activities that demand dynamic, deliberate play. And I’ll define dynamic in a second. And take place in novel outdoor environments. As you know, dynamic basically means there are five categories of functional fitness, strength, stamina, flexibility, agility, and balance. All five need to be trained over time, all five decline over time. All five are very trainable. So dynamic is one word for all five at once. And bonus, when activities are dynamic, when the brain has to coordinate strength, stamina, and balance at the same time, for example, that not only does a bunch of good stuff for the body from an exercise perspective, but dynamic motion boosts the angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Two big fancy words, but angiogenesis, birth of new blood vessels in the brain that support neurons, and neurogenesis is new neurons. And you want to fight off Alzheimer’s and dementia preserve cognitive function, you need new neurons. So dynamic motion isn’t extra, it hits all the physical categories, but it also helps you preserve the brain. It’s also one of the reasons that action sports are such great anti-aging tools. They’re phenomenal for it. But that’s the formula.

Practice vs. play

When we do deliberate practice, the best we’re going to get is incremental advancement. And you’re going to get a little bit of dopamine from goals. With deliberate play, you’re going to get that dopamine, a bigger hit of dopamine. You’re also going to get endorphins, which is what underpins play. So you’re getting two really potent reward chemicals instead of one. So you’ve got a much better chance of increasing learning. And with deliberate play, deliberate practice, there’s one right answer. I did the thing I did before and a little bit better. With deliberate play, there’s only one wrong answer. I did the thing I did before. Everything else is the right answer. So there’s a lot of feel good neurochemistry and less shame and embarrassment.

Flow in business environments

Flow is becoming really fundamental for business. The stat I always like to point to is McKinzie, they spent 10 years trying to figure out how much more productive top executives are in flow versus out of flow. They went around the world and they asked executives, CEOs, C-suite executives, and I’s self-reported and so grain of salt with the numbers, but on average they reported being 500% more productive. That’s enormous. What’s so weird about that number is it’s not out of line. When the Department of Defense measured how much faster soldiers learn in flow was 245% faster than normal. When they measured how much we boost creativity in flow at the University of Sydney, it was 600%… if the competition is going to be a thousand more percent more productive than you are, if they get their employees to spend two days a week in flow, what are you doing?

Is your business looking at the wrong demographic?

We gain access to new levels of intelligence, wisdom, creativity, and empathy in our 50s. I have trained a ton of CEOs, met a ton of CEOs, worked with a ton of CEOs, had dinners with a ton of CEOs, and often the conversation, I’m sure this is your experience as well, is about hiring for peak performance skills or training them. Whenever that conversation comes up, my first question, probably your first question as well is, “Well, what skills are you really interested in? What are you trying to get? What are you trying to do?” Over the years, I’ve heard two answers and usually they come together. I want creativity and innovation because the rate of change in the world is blitzkrieg. How do I keep pace if we can’t out-innovate the competition? I hear that all the time. I need intelligence, I need creativity. I need innovation. Or I hear I need empathy, wisdom and those kind of emotional intelligence skills because I can’t do my job without team performance. I can’t do team performance without psychological safety and cooperation and collaboration.

The future of work

The best companies are companies that figure out how to use humans and AI. I think the best companies are also going to be the companies that have older and younger workers and really blend them together and get the best out of both. If I’m talking to business leaders, those are the messages. If you’re not training flow, what the hell are you doing? Because the competition sure is. Two, if you’re looking for your dream workers, if you can screen for adults who regularly engage in challenging creative and social activities that demand that formula, some variety that that’s a pretty good barometer for, oh, are they going to be successful in their 50s and 60s? Do they have what we want? These are dream workers.